In New South Wales coal mining is big business, with mines hidden beneath ordinary looking forests extracting millions of tonnes of coal each year. However once the coal is removed, an empty void is left behind – and the resulting land subsidence impacts road and rail networks on the surface.

This is an incomplete list of infrastructure that has had to be modified, replaced or rebuilt due to underground mining.

A quick introduction to longwall mining

The Total Environment Centre provide us some background to longwall mining in New South Wales.

Longwall mining is a form of underground coal mining where ‘panels’ of coal are mined side by side separated by narrow ‘pillars’ of rock that act as supports.

A long wall panel can be up to 4km long, 250-400m wide and 1-2m thick. Chocks are then placed lines of up to 400m in length to support the roof.

Coal is cut by a machine called a shearer that moves along the length of the face in front of the chocks, disintegrating the coal, which is then taken by a series of conveyors to the surface.

As coal is removed, the chocks are moved into the newly created cavity. As the longwall progresses through the seam, the cavity behind the longwall, known as the goaf, increases and eventually collapses under the weight of the overlying strata.

This collapsing can cause considerable surface subsidence that may damage the environment and human infrastructure.

Longwall mining in NSW began in 1962. In 1983/84 it accounted for 11% of the state’s raw coal production. This had increased to 36% by 1993/94 and stood at 29% in 2003/04.

Nearly all of the coal mined in NSW lies within the Sydney-Gunnedah Basin and in the five defined coalfields of Gunnedah, Hunter, Newcastle, Western (in the Lithgow / Mudgee area) and Southern (in the Campbelltown / Illawarra area).

Virtually all coal mining in the Southern and Western coalfields is underground.

Douglas Park Bridges, Hume Highway

The first example of modified infrastructure I found was the 285 metre long twin Douglas Park Bridges, which carry the Hume Highway 55 metres above the Nepean River.

The concrete piers having a large steel brace attached where they meet the bridge deck.

The bridge was designed in 1975 by the Department of Main Roads, and did not take land subsidence into consideration, as the Department of Mines indicated mining that they would maintain a coal mining buffer zone around the bridge.

However by the late-1990s approval was given to BHP Coal to expand longwall mining at thier Tower Colliery towards the bridge, provided an extensive monitoring program was put in place.

The impact on the bridge once mining was complete – the abutments were 10 mm closer together, piers had sunk up to 18 mm, and the piers at one end had moved 48.6 mm east.

In the years that followed, the movement in the bridge had worsened, and so in 2007 BHP funded a $9 million project to realign the bridge.

The northern Abutment had moved 57mm, the first Pier around 40mm and the second Pier around 20mm. The next piers were stable.

Because of the different movements, the deck was in a unnatural form and that’s why the bridges had to be realigned. Works had to be proceeded with a minimum of bridge closures.

On the abutments, pot bearings had to be replaced with sliding bearings, which required 4 x 200 tonne jacks to lift the deck. To be able to lift the deck at the Piers, we installed a 40 tonne steel structure to create a lifting base around each Pier.

The realignment was done using 6 x 50 tonne jacks. Once the movement was complete, the bearings had to be welded or clamped to fix the deck to the Piers.

However while this work was still underway, the NSW Government approved further mining was approved beneath the bridge, but this time with a network of 400 sensors collecting deformation data 24 hours a day, along with inclinometers linked to an early warning system.

Trackside solar powered gizmos

Alongside the Melbourne-Sydney railway outside Picton, I found an multiple sets of solar powered instruments connected to the tracks.

And a few kilometres away outside Douglas Park, I found some more complicated looking systems.

Complete with fixed structures for the installation of surveying equipment.

These systems monitor movement in the railway due to mining at the SIMEC Group Tahmoor Colliery and South32 Appin Colliery respectively.

Risk mitigation on the Hume Highway

BHP Billiton Illawarra Coal’s Appin Colliery also passes beneath the Hume Highway at Douglas Park, with land subsidence running the risk of distorting the base of the road pavement. The solution – cutting up the road.

Modelling studies concluded that cutting slots through the existing pavement would be an effective method of dissipating compressive stress in the bound sandstone subbase. As a result of these analyses, the Technical Committee adopted a management strategy where slots would be installed prior to mining.

Sixteen slots were cut in the pavement, eight in each carriageway, directly above the proposed Longwall 703. A further twenty six slots were cut above Longwall 704, for which mining has now started. The spacings of the slots were based mainly on subsidence predictions, with extra slots added within a zone of geological structure.

The Technical Committee recognised that pre-mining slots would probably not be able to accommodate all potential subsidence movements. In particular, irregular subsidence movements could develop, the locations of which could not be identified prior to mining, resulting in locally high compressive stresses in the pavement.

The Technical Committee recognised that additional slots could be installed proactively during mining based on actual monitoring data prior to compressive stresses in the pavement becoming sufficient to result in stepping. Materials, labour and equipment were available to install a new slot within a required 48 hours, with a target to install within 24 hours. This was undertaken on 5 occasions during mining.

Fibre optic sensors were also installed to monitor the movement of the road surface.

BHP Billiton’s Illawarra Coal has embedded three kilometres of fibre optic cables in the Hume Highway to track subsidence caused by a longwall mine that runs under the road.

Illawarra Coal uses fibre Bragg grating sensors to measure temperature and strain at ten-metre intervals along the road’s pavement to detect any forces that could damage the road.

Illawarra Coal’s in-pavement monitoring system is connected to a site-based bank of interrogators that analyse the raw data on a real time basis.

“All data is transferred via wireless network link and is maintained on a web server which is managed by one of the key stakeholders,” a BHP Billiton spokeswoman told iTnews.

“The captured data is compared against pre-determined triggers and has the capability to initiate mobile phone SMS-generated alarms if required for appropriate response as determined by the trigger.”

Replacing a railway tunnel

Just outside of Tahmoor was Redbank Tunnel – a 315 metre long double-track tunnel completed in 1919 as part of the duplication of the Melbourne-Sydney railway.

But there was a problem – the nearby Tahmoor Colliery, established in 1975, and expanded in 1994 and 1999.

A further 4.5 million tonnes of coal was located under the tunnel, and Xstrata wanted to expand the mine yet again to extract it, which would destroy the tunnel.

Tahmoor has now undertaken modelling of subsidence impacts on Redbank Tunnel as a result of mining. This modelling has concluded that subsidence impacts would be significant (up to 1130 mm of vertical subsidence) and likely would impact on the structural integrity of the tunnel, resulting in a risk to rail safety on the Main Southern Railway Line which runs through the tunnel.

So their solution – move the railway.

On 21 December 2010, Tahmoor submitted an application to the Department seeking to modify the Minister’s consent (DA 67/98) to allow for mining impacts within Area 3, and thereby to support the proposed mining of these longwalls. In order to avoid the potential impacts on rail safety, Tahmoor proposes to build a major deviation of the Main Southern Railway line for 1.9 km around the tunnel. The modification would also involve construction of a new overbridge to facilitate landowner access to their property once the rail track has been completed.

And decommission the redundant tunnel.

If Redbank Tunnel was left open after it is bypassed, then it is likely that some sections of the Tunnel’s masonry lining would experience cracking, shearing and localised spalling and possible collapses as a result of mining subsidence. Tahmoor therefore proposes to fill the tunnel with material excavated during construction of the proposed deviation, mitigating any potential safety hazards to people who might enter the tunnel and reducing subsidence to the natural surface above the tunnel.

Reshaping the landscape.

Assessment Report: Tahmoor North Mine, Redbank Rail Tunnel Deviation Modification

Work on the deviation commenced in June 2012, with the first train using the new route in December the same year.

Rebuilding a bridge

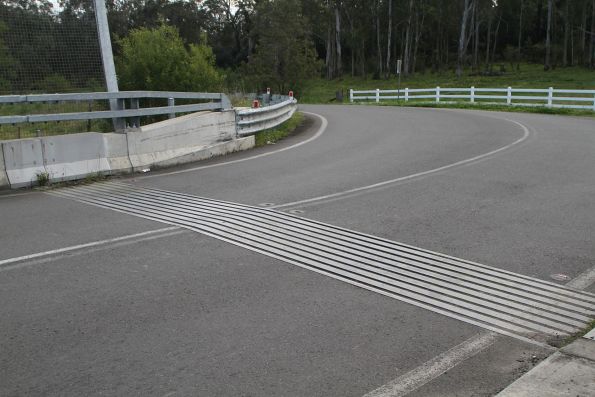

While chasing trains around Picton, a strange looking bridge caught my eye.

The expansion gap looking far too big for the size of the bridge.

It turns out coal mining at Tahmoor Colliery was also the driver here.

Tahmoor Coal Pty Ltd is currently replacing an existing bridge over the Main Southern Railway Line near Picton in NSW, due to proposed mining works. The new bridge is located immediately to the west of an existing brick arch bridge. The rail overbridge is an asset of Transport for New South Wales with Wollondilly Shire Council owning the connecting road.

The new overbridge is required because of potential subsidence impacts from scheduled longwall mining activities in the area in late 2015 which would compromise the safety of the existing bridge structure. The project also involves realignment of the road approaches and the demolition of the existing bridge.

A key issue in the design was the articulation of the bridge which had to cater for large opening/closure movements and large differential vertical and horizontal movements between the two ends of the bridge. A large movement modular deck joint and large movement sliding spherical bearings were adopted to accommodate these potentially large mine subsidence displacements.

Construction commenced in June 2015 and was completed by November the same year.

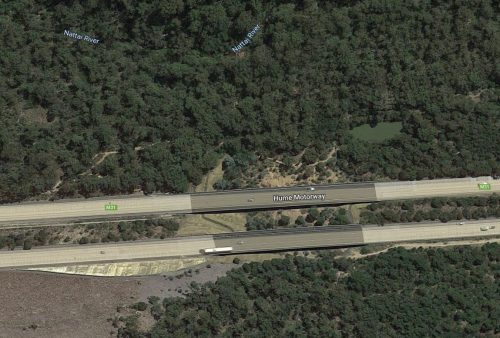

Landbridges on the Hume

This pair of bridges on the Hume Highway outside Mittagong don’t look at unusual from above.

Or from the road.

But they don’t actually span a watercourse.

But were built in 2000s to bridge a section of land affected by mine subsidence.

Plan to bridge the Hume Highway at Mittagong

5 June 2001Working with the Federal Department of Transport and Regional Services (DOTARS), the Roads and Traffic Authority (RTA) has commenced preliminary work on the upgrading of the Hume Highway on the Mittagong Bypass.

The south and northbound lanes will be re-built and two new three-lane bridges constructed on this major interstate road corridor as a result of geological changes that have damaged the road surface and surrounding region over time.

To maintain travel conditions for the 16,000 vehicles using this section of the highway every day, the RTA will receive an initial $6 million from the Federal Government to complete planning and to construct median cross-over lanes. These will allow traffic to switch between the north and southbound carriageways once construction of the bridges has commenced.

The crossovers will be located near the Nattai River and Gibbergunyah Creek bridges and are expected to take two months to build.

During construction, lane restrictions will be in place in the area from 7am to 6pm Mondays to Fridays and from 8am to 1pm on Saturdays.

“In recent years, engineers have detected a subsidence in the road caused by the unique geology of the area. However, the current rate of ground movement is extremely slow and presents no short-term risk,” an RTA spokesperson said.

“The area has a very complex geological history, including mining activity at the adjacent Mount Alexandra Coal Mine from the 1950s to the 1970s.

“To ensure the highway continues to provide high standard travel conditions, work on the crossovers has commenced, with construction of the bridges expected to begin later in the year for completion by the end of 2002.”

The RTA expects to let a contract for the bridge works in October. The twin three-lane bridges will be supported by concrete pylons sunk 10 metres into the bedrock and protected from possible future earth movement by steel casings.

The southbound bridge will be built first and then operate temporarily as a single carriageway road carrying traffic in both directions during construction of the second bridge.

“The Hume Highway is Australia’s most important interstate road artery, with funding for improvements and maintenance a Federal Government responsibility,” a Department of Transport and Regional Services spokesperson said.

“Accordingly, the cost of the new bridges will be fully funded by the Federal Government.

“Both the Federal Department and the RTA are working to ensure this essential road route is upgraded quickly and with minimal inconvenience to the travelling public.

Telephone trouble at Tahmoor

Even the Telstra network wasn’t safe from mine subsidence at Tahmoor.

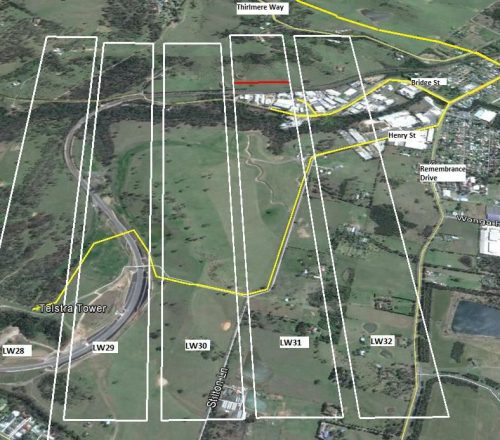

As part of the planning for mining longwall LW32, Tahmoor Coking Coal Operations has identified surface assets which may be affected by the mining operation in Tahmoor north area. Some of these assets belong to Telstra and are part of Telstra’s infrastructure in the area.

Telstra’s major assets in the area are: Tahmoor telephone exchange which is located on the north east corner of Thirlmere Way and Denmead Streets and Picton telephone exchange which is Menangle Street.

As mining has continued north of the telephone exchange the potential for impacts on the major network cable infrastructure has changed as now the longwalls are commencing to impact on the Picton telephone exchange area and the optical fibre cables and copper network to the south of Picton.

The planned longwall mining covering the area.

Management Plan – Longwall Mining beneath Telstra plant at Tahmoor and Picton NSW

With the critical parts of the network being:

a. Optical Fibre Cable – this is predominantly due to the nature of the cable in that it is only able to sustain relatively low ground compressive and tensile strains before the external sheath transfers the strain to the individual fibres within the cable. When this occurs the individual fibres have limited capacity to tolerate tensile or compressive strains before they cause interruption to or failure of transmission systems.

b. Aerial Cable – Aerial cable anchored at adjacent poles or from pole to building can be impacted by ground tilt. Where poles are affected by ground tilt the top of the pole can move such that there is a change in the cable catenery with the potential to either stretch the cable or reduce the ground clearance on the particular cable.

And somehow the legacy copper network got off lightly.

Generally the more extensive Main and Local copper cable network is more robust and able to tolerate reasonable levels of mining induced ground strain. The interaction is complex since the network comprises of very small cable of 5mm diameter up to heavily armoured 60mm diameter cables spread diversely across the entire mining area.

Footnote: and the environment

Water being lost to reservoirs.

NSW’s top water agency has called for curbs on two big coal mines in Sydney’s catchment, saying millions of litres of water are being lost daily and that environmental impacts are likely breaching approval conditions.

The ground is bulging and cracks are reaching from the surface to the coal seam in a section of Sydney’s drinking water catchment that sits above a mine, according to an independent study commissioned by the state government.

Flows from a “significant” water source for one of Sydney’s dams are turning orange and disappearing beneath the surface because of an underground coal mine that is slated to expand to beneath the reservoir itself.

180 tonnes of concrete pumped into a creek.

It was meant to be a remediation program to repair extensive mine subsidence damage to Sugarloaf State Conservation Area in the Lower Hunter. Instead it turned one environmental disaster into another. Contractors working for coal giant Glencore Xstrata pumped more than 180 tonnes of concrete into a tributary of Cockle Creek at Lake Macquarie.

And yet new mines are approved beneath reservoirs.

The Berejiklian government has given the nod for the extension of coal mining under one of Greater Sydney’s reservoirs, the first such approval in two decades.

The Planning Department earlier this month told Peabody Energy it could proceed with the extraction of coal from three new longwalls, two of which will go beneath Woronora reservoir.

All of this makes a few damaged bridges and cracked highways pale in comparison.

Further reading

- Mine Subsidence Community Guide (Mine Subsidence Board)

- Impacts of longwall coal mining on the environment in New South Wales (Total Environment Centre, 2007)

- Impacts of underground coal mining on natural features in the Southern Coalfield (NSW Government, 2008)

The Redbank Tunnel diversion here reminds me of the UK’s (technical) first ever high speed rail line – amazingly given what’s happened since, opened within the last 40 years:

https://www.networkrail.co.uk/stories/the-architecture-the-railways-built-the-selby-diversion/

I’d read about the Selby Diversion before – I guess the difference with the Redbank Tunnel diversion is it was designed to the same ‘goat track’ standards as the rest of the Main South line.

[…] Coal is big business up in New South Wales. […]